This book is a classic in Thailand and has been turned in several theatre-plays, movies and tv-series. The Thai monarchy is constantly in the background throughout the book with Four Reigns referring to the reigns of four different Kings. As the monarchy is a very sensitive topic here and impossible to criticize due to the strictest lese majeste laws in the world, I already knew that the book would probably be propaganda for the royalty. But this in itself could make for an interesting read; seeing how the Thai history is written down in novel form in the way the Thai establishment wants you to understand it. Especially when it includes the death of King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII), who died as an 18-year old in an “accident” with a gun-shot in his head. This death has never been clarified, although this didn’t stop three servants from being executed on charges of conspiracy to kill the King. This incident becomes even more interesting when you take into account that the author, Kukrit Pramoj, was an important politician himself at the time. His brother Seni Pramoj, who basically became the first Thai Prime-Minister after WW2 just a few years earlier, played a prominent role in the aftermath of the King’s death. He accused the then current Prime-Minister Pridi Banomyong (a socialist) for being responsible for the King’s assassination, which was by all accounts extremely implausible. The Pramoj brothers, royal descendents of Rama II and part of the then newly founded Democrat Party, cooperated a year later in a military coup to oust the government, which saw Seni Pramoj rewarded with a high position in the cabinet of the new government (that ironically was ousted by yet another military coup 112 days later).

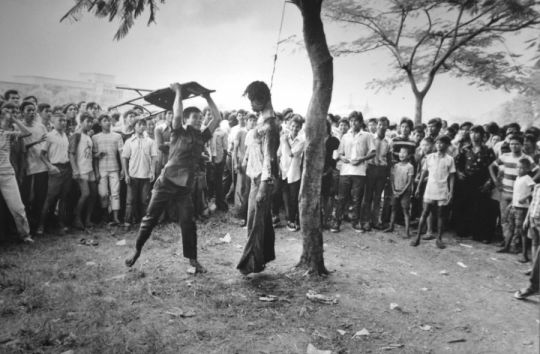

With this background the book gets another dimension. It is not just a novel for entertainment, but it also promotes an ideology that corresponds with the political viewpoints (and interests) of the author, who was Prime-Minister himself for year in the turbulent Thai mid 70s. It’s the ideology of royalists and reactionary conservatives, that talk of freedom and democracy, but will gladly support a coup against an elected government when it threatens the established establishment (be it the socialist threats of the past or today’s Shinawatra family), yet carefully balancing between leftist populist sentiment from the people and the visible and less visible hands that interfere in Thai democracy to this day. The short Prime-Minister terms of both the Pramoj brothers in the 70s are most illustrative of this, particularly Seni Pramoj’s last term as Prime-Minister in 1976, in which he was ousted (again) a day after the Thammasat Massacre. Since Thailand became ‘democratic’ in 1932 it has seen 17 different constitutions and over 20 mostly bloodless coup d’états, with more than once the military doing a self-coup against its own government.

Thammasat University Massacre 6 October 1976. Pro-democracy students were massacred by paramilitary forces that received support from the monarchy. None of the perpetrators have ever been brought to justice. Modern Thai history books skip the event or play it down as a “misunderstanding” between the two sides.

This book explains how Thai people are meant to see the world. If Ayn Rand´s “Atlas Shrugged” defines an ideology that explains modern America with all its ruthless profiteering, then “Four Reigns” should be seen as the book that defines mainstream Thai ideology or “Thainess” as they call it. The basic tenets of this “Thainess” can be summarized as loyalty to the Nation, Religion, and the Monarchy. In 1981, Kukrit Pramoj writes in the preface of this English version of the original Thai book from 1953 that he hopes that those friends of Thailand who do not read Thai, will now “gain a little more understanding towards us”, implying that farang can never truly understand “Thainess”, which is also the common argument from many Thais when you are critically discussing the elephants in the room of Thai politics (even when you’re Thai). And indeed, the book puts out a defense of the Thai ideology that you regularly run into when you live here. While it explains many specific details that were new to me, in general terms it confirmed more what I had already suspected. Rather that changing my outlook towards Thai society, it strengthened some of the more negative thoughts I already had.

The characters can be seen as caricatures, outlining the values that Kukrit Pramoj wants to either promote or put in a negative light. That is not to say that all the characters are flat and one-dimensional, at least not more so than characters in novels usually are, but the characters do tend to be the perfect stereotypes of their times and the values they hold. Some of the characters are extremely sympathetic, like the main-character Phloi for example. The story follows her life, as she is put into the Grand Palace as a 10 year old girl and later lives with together her high-society husband. The book basically explains Thai history in that period through Phloi’s eyes, mostly based on her relationships with the people around her.

Phloi portrays the ‘ideal’ Thai woman; she is perfect, beautiful and completely flawless throughout the book. At times the book almost reads as a guide on how to be a proper Thai woman, which of course comes down to fully sacrificing yourself to your husband at all costs: being there for him at all times; being a good cook; taking care of the kids all by your own; never holding your own opinion against him, keep it for yourself when you disagree with what he says; don’t even dare to be insulted when he fathered a child without ever telling you; and to suggest him, when he feels depressed, to have more than one wife (or extra-marital affairs and massage parlor visits as it would be in modern Thailand); and did your potential partner cheat on you? Fully forgive him in the sweetest of words (all these examples are from the book). Although things have thankfully changed quite a bit in Thailand, you can still recognize much of it. Some feminist emancipation is still drastically needed in this country.

Just as Phloi is written down as the ideal Thai woman of her times, she is also portrayed by Pramoj as extremely likeable. This trick of making all the characters that support Pramoj’s ideology pleasant and those opposing not-so-perfect is used throughout the book. All the royalists in the book are virtuous, while the bureaucrats that take control after the absolute monarchy is dissolved are all clumsy, self-interested and greedy. The characters of royal blood however, from the Kings (that are always at a distance) to a minor princess like Sadet, who adopts the young Phloi in the Grand Palace, are described as absolutely perfect and virtuous, devoid of any negative characteristics. They are all handsome, well-behaved, treating everyone with affection and being perfect dutiful servants towards their subjects. From time to time, one can overhear conversations of the King or Queen talking to commoners, knowing about all their personal issues. The Queen knowing the name of this peasant she had met many years ago, the King talking with this old farmer without teeth as if they were friends, “nothing too big or small for his wisdom and compassion”. It’s the classic propaganda that we in the West often ridicule, think of Kim Yung-il’s fieldtrips and the corresponding photo-ops. Thailand is however filled with similar photos and videos of King making fieldtrips to all corners of the country, inspecting the thousands of royal development projects, for which public accountability and assessment of success are of course completely out of question.

It’s the basic outline of the Thai ideology in which all the politicians are seen as greedy and bad, while the royals are ‘above politics’ and keep the country on track. The King is the source of all that is good; he’s selfless, never smiling or enjoying earthly pleasure, but dedicating his life to improving the Thai nation. The (current) King is portrayed as a brilliant scientist telling politicians what to do, as one who is (literally, I kid you not) capable of providing rain for the crops, and as a bringer of justice (with the annual royal pardons). Politicians however can do no good and are the source of all misery. In history classes Thai children will learn of all the good things done by the royals, but young Thais are unlikely to know much of statesmen as Pridi Banomyong or Puey Ungpakorn.

Of course we also get the revisionist history of the Thai monarchs as true democrats. The role of Rama VII in the three years after the revolution is mostly ignored. In reality he stifled the democratization process by co-opting the military side of the Promoters (in opposition to Pridi and others), and attempting to create a limited monarchy rather than giving up his executive and legislative powers as in Europe’s constitutional monarchies1. In Thai ideology however, the king is ‘above politics’ and would never intervene for its own interests, so the focus instead is on how the new bureaucrats in power (including Phloi’s son An 2) immediately start constricting freedom of speech (which did happen, but as if there was such thing as freedom of speech under absolute monarchy?). Rama VII is portrayed as being as democratic “as any of them [in the government], if not more” (496). When Rama VII finally decides to abdicate in 1935 after 3 years of uneasy cooperation with the government, Ot (the most agreeable son) tells her mother “Democracy hasn’t been with us for very long, and now we’ve lost one of its staunchest champions”.

Besides the revisionist fairy-tale of Thai monarchs as true democrats, another major element in the ideology of “Thainess” is spirituality and religion. While nowhere becoming super-natural or turning into downright fantasy, throughout the book the Thai’s superstition is quietly supported. The rituals and amulets always seem to help, at least nowhere future events contradict expectations raised by their practice and usage. Many of the future events, especially the dying of characters close to Phloi, are in some way predicted by signs or feelings. The end of the four reigns in particular is always preceded by major signs, especially the death of King Chulalongkorn. The appearance of the Halley’s Comet in 1910 worries Phloi as it must be a bad sign, she is then calmed by her husband some days later, telling her that it had nothing to do with them at all, as the comet must have signaled the death King Edward VII who must have accumulated much, much, much merit, so that even they in Thailand could see it (sure enough it is always good to prop up foreign monarchies a bit, in support of your own3). But of course, less than one page later it is announced that Rama V unexpectedly died, even though he died all the way in October, five months after the death of King Edward VII and the appearance of the comet. Unsurprisingly, during Rama V´s cremation the sky darkened, thunder struck and rain came pouring down (280-284). But at least this cliché however could really have happened considering it took place in Thailand’s rain season.

Then there are the prophecies, we are reminded how the end of absolute monarchy in 1932 coincides with the supposed Rama I’s deathbed prediction that the Chakri dynasty would last no longer than 150 years. Karma is also a constant concept that is referred to. It is believed that making merit, either in your previous life or through your current life, will lead to a good life. Whenever something bad happens in your current life, it must be because of something you have done in your previous life. Buddhism here is always in support of the status quo and the establishment. If you are born into lower-class, it must be your own fault and you can make merit by suffering your way through it rather than rebelling, so you will be better off in the next life. The King however must be the highest of reincarnations, having accumulated enormous amounts of virtue in previous lives, and should therefore not be put into question.

Thailand’s Buddhism is deeply connected to the monarchy. In every wat (temple) one can find portraits of King Bhumibol and yellow flags of the monarchy. The concept of Divine Kingship originates both from Hindu Brahmanical cults of the devaraja and deification of the kings, and Buddhist-based ideology of the dhammaraja monarch whose status is a product of his unmatched virtue. To put the importance of this in perspective, it is instructive to go back to the writings of H.G. Quaritch Wales. He was a British anthropologist that worked in Lord Chamberlain’s Department in the Court of Siam as an adviser to Rama VI and Rama VII, and who published a study on the functional value of Divine Kingship in 1932. He was warning against the breakdown of customs and rituals together with the spread of Western education and modern skepticism, as this combination would threaten the social integrity of the state. His book explains in detail the importance of symbolism and religious ceremonies in strengthening the monarchy. He (1932: 192) writes about the great sociological value of prostration (which was banned by King Chulalongkorn), arguing that the lack of customs and rituals displaying reverence to the monarchy leaves the door open to “… the dark teachings of communism, or whatever doctrines may chance to catch the ear of the masses, to step in and hasten the work of social destruction” (1932: 7).

The monarchy, as an institution, has therefore been central in maintaining Thailand’s strict hierarchical system. Bolstering the divine aspects of the monarch has worked as a great counter towards ‘dangerous ideas’ of social equality. It is then also no coincidence that prostration, even though banned in 1873 by King Chulalongkorn, has actually been encouraged and returned in the current reign (see popular talkshow host Woody interviewing Princess Chulabhorn and sharing her pet dog’s food). It also no surprise that when Thailand became the United States’ most important ally in fighting communism in South East Asia, the “American information officials in Bangkok […] concluded that USIS funds could not be better employed than in spreading the likeness of His Majesty”.

For the ruling classes, the Thai ideology espoused in Four Reigns has been an incredibly successful answer to any call for social justice and equality. Putting it in a historic context, this book has been Kukrit Pramoj’s counter to the appeal of Pridi’s more socialist ideas. Hierarchy, for instance, is not questioned anywhere in the book. Throughout the book it is suggested to treat the servants and everyone lower in the social hierarchy properly, but the existence of this hierarchy in itself and unfairness of it isn’t acknowledged anywhere. Instead we have the most likable characters criticizing how there is too much freedom after the end of the absolute monarchy, too much freedom to stage a revolution against everything and everybody, with our likable main-character Phloi being appalled to hear stories of pupils staging revolution against their teachers and temple boys against their monks (484). All the characters in the book just accept hierarchy as a natural given fact of life, with all those lower in caste carrying on accordingly. Phloi for instance starts out in the book as a 10 year old girl of low importance, but despite this, she still has her own loyal and obedient maid Phlit that faithfully follows her around without questioning anything until the day she dies. The high society is sometimes portrayed as fashion-crazed, spending money on unnecessary things, but generally as virtuous and enlightened. And at least they know how to carry themselves around, unlike those darned bureaucrats and businessmen that worked themselves up from their lowly simple backgrounds after absolute monarchy ended, they are greedy and always behave frustratingly socially awkward when they are at a party or a ceremony, not knowing the social mores and the contemporary hi-so etiquette. At least, that is essentially the contemptful portrayal they receive from Kukrit Pramoj in Four Reigns.

The exploitation on which wealth of the royalty and upper classes is built is nowhere explored. Instead we hear commoners mourning the downfall of the expensive villas that turn into ruin, after its royal residents flee the country after 1932. Interestingly, traces of sufficiency theory can be found a couple of times. Commoners leading simple lives without complaining are celebrated throughout the book. Particularly noteworthy is the conversation of the difference in poverty between England and Thailand when Phloi´s son Ot comes back from his overseas education. According to him, the rich in England are colossally rich and a large fortune in Thailand would be considered laughable over there. The poor in Thailand on the other hand are much more fortunate than the poor in Europe, as they don’t risk freezing to death in the winter, and the food is easy to come by with plenty of fish, fruit and vegetables growing. This rather contrived dialogue then continues on to ridicule England’s upper-class’ hobby of fox hunting (431).

In Thailand 2012 it is shocking to see how little has changed, the affluent classes still take the obedience of those lower on the social ladder for granted, and are infuriated whenever those dark-skinned “uneducated” peasants start to assert themselves. If you exclude the red shirt rallies in recent years however, it is bizarre how the Thai’s social hierarchy is still strictly adhered to, with society’s lower parts politely serving and looking up to those above them, quietly accepting the injustice of it all and suffering through their lives as proper Buddhists4.

So what to make of all this? Four Reigns is a propaganda book outlining the ideology of “Thainess” that has continued to serve the upper-classes of Bangkok for decades. It reinforces the strict social hierarchy, promotes the deification of the royalty and the revisionist history of the Chakri monarchs as enlightened democrats with the myth of them being ‘above politics’, it prescribes the gender roles of Thailand’s patriarchal society, and quietly supports Thai´s superstition, and so on. It is filled with contrived and manufactured dialogue in support of “Thainess”. Characters are used as devices, whether they are successful or unsuccessful, likeable or less likeable, depends on the moralistic message for which the author uses them. Of course, this is not unique to Four Reigns. No book is immune to ideology; it is implicit in every human expression. But this book is intentionally written by Kukrit Pramoj in order to convince the Thai population of his idea of “Thainess”. For me, as a reader with rather different political ideas, it then becomes confusing to judge or even enjoy the book in a normal way.

I made the analogy before, but I can imagine that it is a similar when you read “Atlas Shrugged”, as a reader you become sort of attached to the character John Galt, while simultaneously despising the values and politics he espouses. There is a similar duality with the main characters in this book; the most pleasant characters are devoted to their monarchs to an extreme that borders insanity. Should you do what Kukrit Pramoj wants you to do and just enjoy the book by buying into its characters, or keep dissenting and resisting the craziness? Personally I found my enjoyment in reading between the lines. What we can do however is to commend Kukrit Pramoj on his accomplishment. “Four Reigns” is a much better written book than “Atlas Shrugged” for one. And while the values espoused in his book served him and his friends politically, there is no doubt that he was also inspired by a sincere love for his country for whatever that is worth.

1 See http://khikwai.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/PRAPOKKLAO.pdf

2 Phloi has four children in the book, all of them caricatures to explain the changes in Thai history in that time. On is the royalist soldier, banished to prison for a decade after participating in the Borawat rebellion. Praphai is the beautiful daughter who exemplifies the changes for women in the modernizing Thailand with her taste for modern fashion and hi-so parties. An and Ot are however among the first upper-class Thais to go abroad for an overseas education. An is the overly ambitious son, is a participant in the 1932 coup and becomes a powerful bureaucrat, who then slowly becomes disillusioned by the new government and regrets his past actions. Ot is the easy-going and most sympathetic son, who is less ambitious than An, but much wiser and constantly in support of the royalty. It’s worth pointing out that An went to study in France like most of the coup plotters including Pridi, while Ot went to study in England like the Pramoj brothers did. I doubt that this is purely coincidental.

3 It might be because I am more perceptive to it here, but it seems I see about the same amount of pictures of the Dutch monarchy as I do back in the Netherlands. The celebrity magazines in Thailand are all about news on European monarchies. The official pictures of the Thai monarchy often include visiting foreign monarchs. And during the British royal wedding madness last year I (and any other Caucasian in Thailand at that time) was hailed several times by Thais sharing their excitement with me, as if care.

4 On a personal note, Phloi’s maid Phlit reminded me a lot of the maid in our own condominium, who works tirelessly from 8am to 11pm, always carrying a smile on her face, and is a similar chatterbox as well.