Where should one begin in reviewing a classic like this one? It was always recommended to me as a forgotten classic, a great critique of markets, ignored by the mainstream, and highly relevant to our times despite being over 60 years old. And relevant it is; it is a great assault on the idea of self-regulating markets, an idea that sadly still seems to inform most of today’s mainstream discourse. There is some uncanny resemblance between the events Polanyi writes about and many of the things still going on in our own neoliberal era. Furthermore, this book is also about the break-down of the market society and its collapse into the Great Depression, which makes it even more relevant considering today’s crisis of capitalism.

The Great Transformation is a work that combines several disciplinary fields of the social sciences which ought not to be separated: anthropology, sociology, history, (political) economy and political science. It’s all in there. Polanyi gives a history of the emergence of the market economy and its social implications. Its greatest strength and what makes it so uniquely different from other books is its rediscovery of society. Society is the perspective taken, rather than for example class (which is dismissed as crude Marxist dogma by Polanyi). When explaining the social dislocations from imposing the market economy, it’s society that suffers and consequently brings forth its reaction. Markets did not naturally evolve or start out of individual acts of barter (NO, people did not barter in ancient societies, anthropologists never found a single society to do so out of the thousands that have been researched). Markets were actually imposed on the people by government intervention from the very beginning. History shows that regulation and markets grew up together, but it was the idea of the self-regulating market that found ground during the Industrial Revolution was a complete reversal of this trend.

In the ‘ideal type’ market economy all production is for sale on the market and all incomes derive from these sales. This means that markets are there for all elements of industry, not just goods, but also for labor, land and money. Interest is the price for money and it’s the income for those that are able to provide it (the financiers); rent is the price for the use of land and also the income for those who supply it (the property-owners); wages are the price for the use of labor and the income for those who sell it (the workers). The market economy assumes that supply at a definite price will equal the demand. Production and distribution depend on prices, for prices form the income that ensure the distribution. The brilliant insight here is of course the recognition of Polanyi that land, labor and money, despite being subjected to the market, are obviously no commodities; they are not produced for sale! That is why Polanyi refers to them as fictitious commodities. The commodity description is entirely fictitious, but this fiction is used to organize them. They are being bought and sold on the market; their price depending on supply and demand. All this to enable the self-regulating market.

A market economy, in which the economic system is controlled, regulated and directed by markets alone, exists only in a market society. As when land and labor are being turned into commodities, it is society itself that is being subordinated to the market. This was utterly new and beyond people’s imagination before the Industrial Revolution. Mercantalism, with all its tendency towards commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected these two basic elements of production -land and labor- from becoming the objects of commerce. For the market society to work, the homo economicus had to appear, the idea that human’s primary motive is to maximize gain. But the early laborer could not be lured into the factory, as he did not feel compelled to make as much money as he could, where he felt degraded by the work. Only the threat of corporal punishment and starvation, not the allure of high wages, would make him sell his labor on the market. The masses first had to be pauperized and forced off the lands before a labor market could come into being. As Polanyi argues, it is much more social status than monetary gain that humans crave.

“Now, what the white man may still occasionally practice in remote regions today, namely, the smashing up of social structures in order to extract the element of labor from them, was done in the eighteenth century to white populations by white men for similar purposes. Hobbes’ grotesque vision of the State –a human Leviathan whose vast body was made up of an infinite number of human bodies- was dwarfed by the Ricardian construct of the labor market: a flow of human lives the supply of which was regulated by the amount of food put at their disposal.”

In rewriting the history of the Industrial Revolution and the establishment of the market society, Polanyi comes up with a highly interesting account of all the contradictions coming out of obscure laws in England at that time. Nobody truly understood the reasons for poverty at that time, often going for morality tales like Hannah More’s Christian suffering (blaming it on drinking tea was common as well!), the connection between a higher total trade and unemployment wasn’t seen. The intellectuals at that time believed the more poor people there were, the more wealth as well. The Speenhamland laws led to a market economy without a labour market and no reliable statistics. It was during this time of confusion that economic theory was founded.

The discovery of economics was astounding. Interestingly enough, back then it was natural science that gained in prestige by its connection to social science (instead of vice-versa!). The triumphs of natural science had been merely theoretical and were of no practical importance, while the discovery of economics critically hastened the great transformation and the establishment of the market society. The creators of machines were mere uneducated artisans who often could barely read or write.

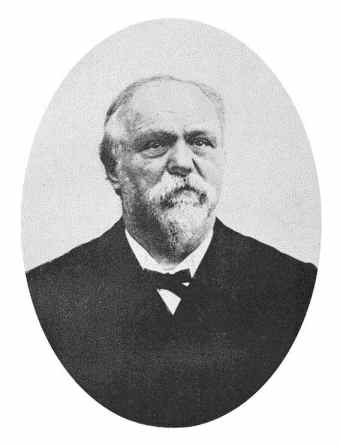

Because of the overall confusion the great minds did not really understand capitalism and many came up with the dues ex machine of Nature, with the most well-known example the Malthussian law of population. They thought of economic society as subjected to laws from Nature rather than human-made laws. Ricardo combined the naturalistic and the humanistic, with the laborer being the only force to create economic value in his theory of value (mistakingly adhered to by Marx according to Polanyi), who was then again subjected by the self-regulating market that followed the inexorable laws of Nature. Polanyi puts the proto-socialist Robert Owen forward as the only person who saw the meaning of it all. He understood that what appeared to be as an economic problem was in fact a social one. In economic terms the worker was certainly exploited and did not receive a fair exchange. But in spite of exploitation, it was the massive social dislocations, degradation and misery that was truly problematic. And here Owen rightly called for legislative interference against the devastating forces from the self-regulating market.

“My life was not useless; I gave important truths to the world, and it was only for want of understanding that they were disregarded. I have been ahead of my time.” – Deathbed statement (November 1858), in response to a church minister who asked if he regretted wasting his life on fruitless projects

But at that time the dominant intellectuals thought differently. The word laissez-faire may come from France in the mid 18th century, it was only in the 1820s that it began to stand for its three classical tenets: for a labor market, the gold standard and free trade. Economic liberalism became a secular religion: “Born as a mere penchant for non-bureaucratic methods, it evolved into a veritable faith in a man’s secular salvation through a self-regulating market”. It is no coincidence that Adam Smith’s constantly quoted “invisible hand” has such a divine connotation. Laissez-faire became a secular faith that was pursued with evangelical fervor in order to make the market economy reality. In the 1830s it suddenly became policy, the 1832 reform created a free labor market, the gold standard became the automatic steering mechanism, and England started to depend on food from overseas sources. Under the self-regulating market the most productive and inventive would be able to survive and the British believed their factories would be able undersell to the rest of the world. This also meant the expansion of the market system on a world scale powered by the might of the British Navy.

But there was nothing natural about laissez-faire. It was enforced by the state, which required enormous increases of centralized legislation, control and intervention to introduce free markets. Furthermore, freedom of contract is not a principle of noninterference as liberals argue; it destroys noncontractual relations between individuals, it imposes atomistic individualistic organization on societies. Laissez-faire was not a method to achieve a thing, it was the thing to be achieved. Paradoxically, the philosophy that demanded the restriction of state activities and intervention, could not but entrust the same state with the new powers and instruments in order to establish laissez-faire. If laissez-faire means the opposite of interventionism, how then can laissez-faire claim to be laissez-faire? And ironically enough, while laissez-faire was planned, the counter-movement against laissez-faire was not. While laissez-faire was utopian, that what Polanyi calls the ‘double movement’ was spontaneous and pragmatic and became successful in the 1860s in protecting a broad range of vital social interests against the expanding market. Liberal economists as Mises, Spencer, Summer and Lippmann have a mistaken interpretation for this double movement, explaining it on impatience, greed and shortsightedness. These writers blame the rise of socialism and nationalism for frustrating economic liberty and they often point to trade unions, Marxist intellectuals, greedy manufacturers and reactionary landlords as the villains in their narrative.

Polanyi also connects the emergence of the market society and the subsequent double movement with colonial expansionism. There was a time that even the tories considered colonies to be a waste, but after the double movement caused protectionism, countries ´irrationally´ stopped trading with each other as much and instead started ´trading´ with the overseas market. As a result the colonial population was subjected to the same kind of social dislocation as the British people were earlier. The introduction of market organization of land and labour broke up the village life and subsistence living. This -much more than the mere brutal economic exploitation- caused massive famines in for example India. And colonial societies were even less capable of protecting themselves against the market forces than the British peasantry.

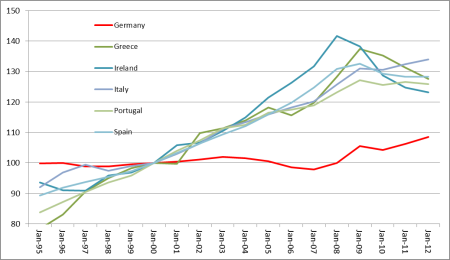

His discussion of the Great Depression and the Gold Standard is of great contemporary relevance. There are many similarities here with the current crisis and the adherence to euro. The European elites are doing everything they can to keep inflation low and maintain the euro while simultaneously imposing austerity and social misery upon the periphery, disregarding the democratic wishes of the people there with more and more technocratic rule. And just as liberal economic theory in Polanyi´s time ignored country differences and their trade imbalances, putting Great Britain on the same rank and footing as Denmark or Guatemala, the creators of the European single market and monetary union conveniently failed to see problems that would come out of a monetary union without fiscal and political union (despite being warned by plenty of people that saw it coming).

Also relevant is his discussion of constitutionalism, which changed in meaning during the demand for popular democracy by the Chartist movement. The Chartists threatened to stop the satanic mills of the market economy during the massive social dislocation of the emerging market society and were violently put down by the authorities. A hundred years earlier Locke´s constitutional safeguards were meant to protect commercial property against arbitrary acts from above (the Crown), but now constitutional safeguards were put in place to protect industrial property from the people. The separation of power that constitutionalism entails was now to separate people from power of their economic lives. The American constitution that put private property under the highest conceivable protection created the first legally grounded market society in the world, where people, in spite of universal suffrage, are powerless against the owners. In our current globalized market society we have what could be called the new constitutionalism (coined by Stephen Gill) in which political-economic structures are shielded from democratic rule and popular accountability in order to grant privileged rights to corporate capital and large investors. The European Monetary Union is a prime example of the new constitutionalism and the soon-to-be implemented fiscal pact will be an escalation in sacrificing democratic participation on macro-economic policy in favor of imposing automatic austerity on the member-states.

Following the new constitutionalism, Polanyi´s discussion of fascism serves as a warning for European’s ongoing malaise: “The stubbornness with which economic liberals, for a critical decade, had, in the service of deflationary policies, supported authoritarian interventionism, merely resulted in a decisive weakening of democratic forces which might otherwise have averted the fascist catastrophe”. The European elites, with their constant separation of economics from popular accountability, with their constant assault on the welfare state, and with their disregard for the democratic wishes of people in the periphery, are very likely to underestimate the social forces they are slowly unleashing by the social misery they impose on the people. The scenes of Golden Dawn mobs beating up immigrants and leftists in Greece, while police look the other way, should speak volumes for the need to heed Polanyi´s warning. To Polanyi the success of fascism in the 1930s is best explained by the failings of the market system. It had nothing to do with local causes, national mentalities, historical backgrounds, it sprang up everywhere. Many fascist movements were in fact non-nationalist. One should actually not speak of a fascist ‘movement’, as fascism relied upon the goodwill of people in high positions rather than popular masses; nowhere fascists took power by an actual revolution, it was always no more than a sham rebellion that had tacit approval of the authorities that pretended to be overwhelmed by force. Between ´24 and ´29 fascism faded away as the market system seemed ensured, but after the crisis in 1930 fascism became a world power in just a few years.

Polanyi considers the victory of fascism to be the result of the liberal’s simple-minded idea of freedom that sees any control or planning to be a denial of freedom. Freedom then degenerates into a mere advocacy for free enterprise, which is reduced into a fiction by the hard reality of giant trusts and monopolies. His last chapter on freedom in a complex society seems like preliminarily answer to the arguments found in Milton Friedman’s Capital and Freedom 18 years later. Without regulation freedom is only freedom for the few. Liberals believe in an illusionary idea of freedom that denies the reality of society, as if all power and compulsion is gone when we engage in contractual relationships in the market economy as individuals. The fascists are the response to the failings of the market economy; they relinquish freedom and glorify power which is the reality of society. It is then up to the socialist to accept the harsh reality of society, but to defend freedom in spite of it, as Polanyi concludes: “Uncomplaining acceptance of the reality of society gives man indomitable courage and strength to remove all removable injustice and unfreedom. As long as he is true to his task of creating more abundant freedom for all, he need not fear that either power or planning will turn against him and destroy the freedom he is building by their instrumentality. This is the meaning of freedom in a complex society; it gives us all the certainty that we need.”

Now 68 years later the word freedom continues to be abused as a simple-minded justification for markets. In our current neoliberal era market-oriented solutions are put forward to every problem. Whenever a government is unable to balance its budget, it often sells one of the tasks it used to fulfill off to the market. Essential parts of the modern welfare state like healthcare, education, housing, are increasingly subject to market forces. But also for credit (see the deregulation of the financial sector – the market knows best) and even for climate change (see cap and trade, CDM, REDD etc) markets are forwarded as the solution. Paradoxically, the solution is in fact the problem. Just as in the old times Polanyi writes of, the technocrats separate society into an economic and a political sphere, and attempt to solve (fundamentally highly political) social problems with ‘depoliticized’ technical solutions. The markets are seen as neutral arbitrators that will lead to a natural and objective equilibrium. Of course, it is not just ideology, turning something into a market is also the politically convenient way out that does not impede on powerful interests.

But to Polanyi markets in themselves are not a problem. It is the self-regulating market that is problematic, as upholding the commodity fiction threatens society and human life. When the commodity fiction is abandoned and labor, land and money are no longer treated as commodities on the market, then the market can, even in principle, no longer be self-regulating. But the end of the self-regulating market and the market society does not mean the end of markets, as they should continue to ensure consumer freedom, to indicate the shifting of demand, to influence producer’s income, and serve as an instrument of accountancy. Here Polanyi, who self-identifies as a socialist, distinguishes himself from many leftists and Marxists that do want to abolish all markets. Polanyi in this day and age seems to be more some kind of radical social-democrat, who looks to reform society by regulation and planning that increases the freedom of all and always protects the individual’s right to nonconformity.

One could wonder how dismissive Polanyi is of Marxism. He did read Marx and accepts the exploitation of the worker in the capitalist system as a given. The most important difference between the two may be one of perspective. To Polanyi it is much more the massive social dislocation from imposing the market society (especially during the phase that Marx would call ‘primitive accumulation’) rather than the purely ‘economic’ exploitation of the worker creating more value than he earns that is important. Instead of the class struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, Polanyi opts for the less antagonistic perspective of society as a whole (the working, middle and landed classes) protecting its general interest against the brutality of the market. The narrative he sets out to defend this perspective is convincing. He faults the ‘economic determinism’ that misses out on society. On Ricardo’s labor theory of value he writes for example: “In a mistaken theorem of tremendous scope he invested labor with the sole capacity of constituting value, thereby reducing all conceivable transactions in economic society to the principle of equal exchange in a society of free men”. Marx adhered to Ricardo’s labor theory of value but added that it was not an equal exchange in a society of free men, but that the laborer was in fact exploited by the capitalist. I am guessing that the problem for Polanyi here might be that this theory of value, be it Marx´s or Ricardo´s, is too individualistic and atomistic, excluding other forms of economic organization, like for example communal. To Polanyi the main problem is of course not the worker being exploited (better to be exploited than not to be exploited at all), but the social dislocations that come out of the establishment of the market society.

Rather than arguing for one perspective or the other it may be best to conclude that one sees different things by using a different lenses and that both perspectives having their uses. I do however think that right-out dismissal of the ‘economic determinism’ of Marxism and other theories is mistaken. He does in fact lack a convincing explanation for the Great Depression. Polanyi looks at failings of the market system and the subsequent double movement, he kind of seems to argue that protectionism then led to the Great Depression, but it remains rather unclear. He certainly does not look or have any kind of explanation for the boom-bust cycle of capitalism and why the markets ‘failed’ at this or that particular time. His dismissal of other theories as the falling rate of profit, underconsumption or overproduction is therefore rather inappropriate.